Novae by Kaiju is the story of Raziol, an apprentice astronomer in 17th century Paris, and his encounter and budding romance with Sulvain, an enigmatic necromancer. Despite their apparent differences, the two find themselves helplessly gravitating towards one another, expanding each other’s understanding of the universe around them. While Raziol teaches Sulvain how the vast emptiness of the sky is anything but, Sulvain slowly introduces Raziol to a whole magical underworld he didn’t know existed, where charms and spells are commonplace, and where the veil between life and death is much more permeable than he ever thought.

How does the symbolism establish the story’s notions of life itself?

One of the core themes of Novae is the acknowledgment that there is much that humanity does not know yet. This is first seen in Raziol and his journey as an astronomer’s apprentice, playing a small part in a much larger institution dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of the discoverable universe. After meeting Sulvain, Raziol slowly realizes that there are whole realms of knowledge that he didn’t even fathom before, not only concerting magic, but also the nature of the afterlife and death itself. Since the dawn of time, humanity has been inevitably drawn to the notion of death, mostly due to the full awareness we have of our own mortality. In an attempt to understand it and make our peace with it, countless stories about the death and afterlife have been told and retold, with each of them employing different perspectives and techniques to give shape to the shapeless. This is where symbolism comes into play.

Credit: Kaiju

A six-panel page.

First panel: A close-up of Viverette as she holds up a pear of tweezers.

Second panel: A close-up of Viverette as she looks up at Sulvain, who is off-panel.

Viverette: Well, what about me? Did you see my wheat spring growing over there?

Third panel: A close-up of Viverette’s hands as she stitches up Sulvain’s clean, bloodless wound. The thread is a bright gold color.

Viverette: Do you know how long I’ll live?

Fourth panel: A close-up of Sulvain’s profiled face.

Sulvain: I do not know, but I hope you’ll live until you are old and grey.

Fifth panel: A close-up of Sulvain’s half-closed left eye from the previous panel.

Sixth panel: A break-out illustration of a golden field of wheat under a dark sky. In the middle of the field, there is a giant, ominous sphere of purple and black darkness.

Sulvain (off-panel): I don’t supposed I’ve ever seen a Magoi’s wheat before… They grow somewhere else, deeper, closer to the source. Not even a necromancer can venture that far and return.

Following ancient storytelling tradition, Navae presents the concept of death and the afterlife in terms the human mind can understand thanks to the use of symbols and establishment of motifs. The clearest of these symbols are the sprigs of wheat that represent human lives. When Sulvain enters the afterlife, he finds himself in a golden field of wheat, with each sprig representing the life span of a single person. Besides the beautiful visuals it creates, the symbol is well crafted because of the metaphor it represents. Just like life itself, wheat must eventually be harvested — reaped, if you will — thus highlighting the inevitability of death. Similarly, just like a sprig of wheat, we do not know when life will be reaped. And finally, the purpose of the wheat is unknown to itself, just how the purpose of life and death is unknown to us. In Novae, however, death and Sulvain do know the purpose: the straw is spun into thread to be woven into a golden cloth, lives reshaped into another tapestry of creation. The thread can also be used to stitch and heal wounds, so these lives also become part of another greater whole. Overall, through the use of this symbol, Novae creates the notion that, across different planes of existence, human lives are always meant to be woven together.

Credit: Kaiju

A single panel.

A row of eight barely lit sillouhetted figures, enveloped in darkness, each carrying a single torch.

Credit: Kaiju

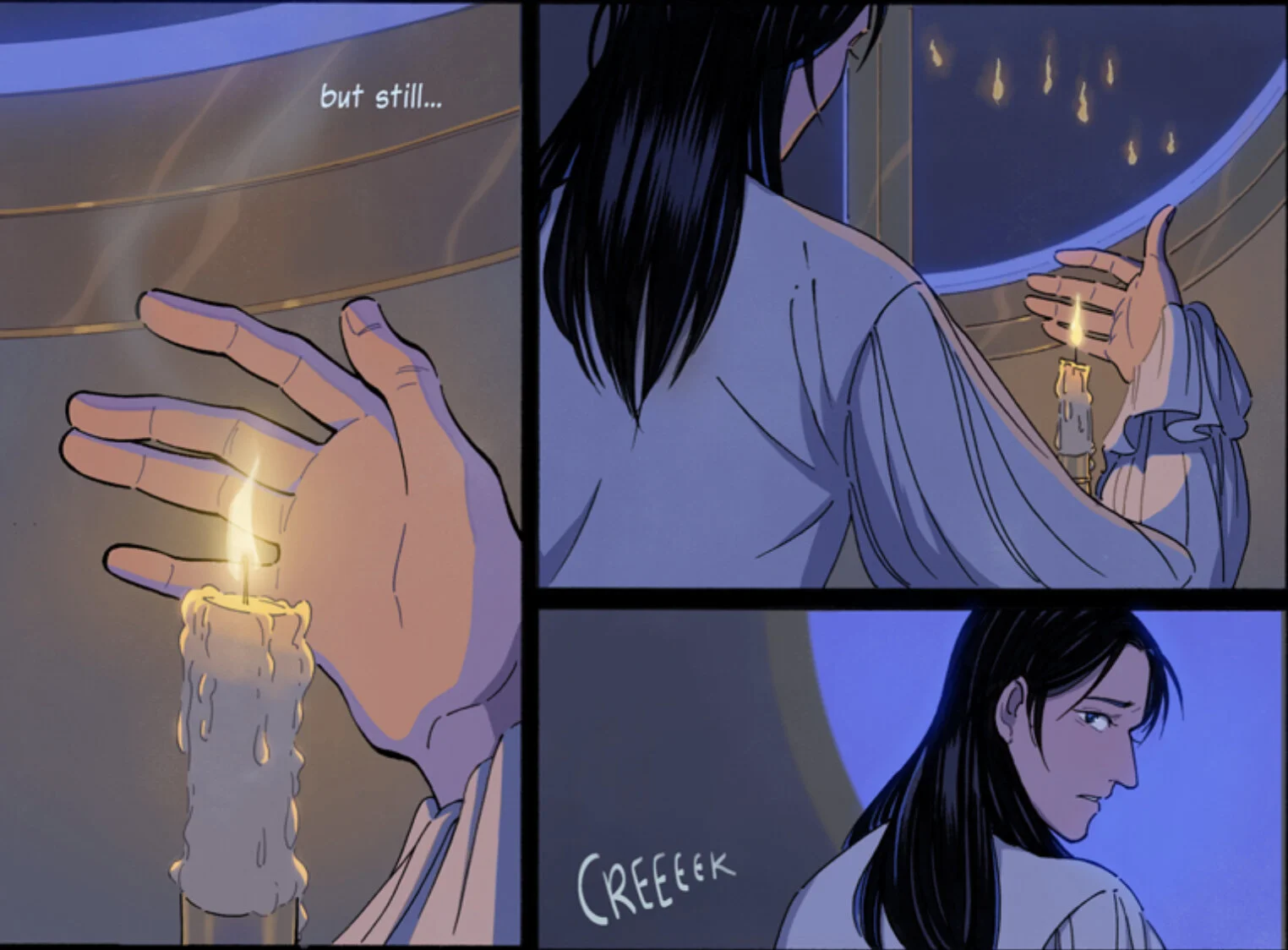

A three-panel page.

First panel: A close-up of Raziol’s hand as he shields a lit candle

Second panel: A rear view of Razor shielding the candle, through the window in the background, a row of torches is visible.

Third panel: A rear view of Razor looking over his right shoulder as he hears a creaking sound behind him.

In addition to the sprigs of wheat, life is also symbolized — albeit in a lesser degree — through the depiction of flames. This connection can be drawn thanks to the visual allusion created by the funeral march seen from Raziol’s window. The way the flames from the torches illuminate the profiles of their bearers creates a fine golden line reminiscent of wheat in the field. Other panels in this scene depict Raziol holding and shielding a candle while he watches the row of torches in the distance. This representation highlights how ambivalent both life and fire can be. On the one hand, both are fragile and can be easily snuffed; on the other, they can be strong enough to weather the elements and provide others with light and warmth. In both cases, nevertheless, purpose of the flames is to form part of something greater by aiding those around them. Through the use of these symbols, it is then safe to argue that Novae presents that life is ultimately meant to be lived in community.