Novae by Kaiju is the story of Raziol, an apprentice astronomer in 17th century Paris, and his encounter and budding romance with Sulvain, an enigmatic necromancer. Despite their apparent differences, the two find themselves helplessly gravitating towards one another, expanding each other’s understanding of the universe around them. While Raziol teaches Sulvain how the vast emptiness of the sky is anything but, Sulvain slowly introduces Raziol to a whole magical underworld he didn’t know existed, where charms and spells are commonplace, and where the veil between life and death is much more permeable than he ever thought.

What effect does the use of sign language in the story have on the reading experience?

Needless to say, dialogue plays an integral role in comics. While sequential art can certainly exist without any kind of text, the medium of comics at its core is characterized by the intrinsic relationship of text and illustrations. This is particularly true when it comes to graphic novels as they require text to move such long stories forward, just like traditional novels do. In general, text in comics mostly takes the form of dialogue — in this way, they’re more like a play than a novel — and this dialogue becomes an essential trait for the characters. Through the way they speak and communicate with the world around them, not only is it possible to get a gist of who they are, but it is also a way to understand the world created by the story. Novae goes one step further by having one of its protagonists communicate through sign language thereby expanding the scope of representation in the medium, as well as providing an excellent point of discussion on the nature of comics.

Credit: Kaiju

A three-panel page.

First panel: Viverette is leaning on her counter, holding her head on her right hand. She is surrounded by colorful butterflies, a golden beetle, and a number of plants, bowls, and crystalware.

Viverette: I see that the little one went to greet you.

Second panel: Sulvain is pointing his index fingers up as he smilies at Viverette off-panel.

Sulvain: The way you enchant, Viverette, it never fails to amaze me.

Third panel: Viverette is laughing, waving off Sulvain’s compliment as he continues to look at her.

Viverette: It’s just a simple search and lead charm, nothing grand.

The notions of sound and movement in comics have been discussed on this blog before; however, Novae brings a whole new perspective on the topic. In a nutshell, because of the visual nature and the sequential structure of comics, the only sense engaging with the text is sight. While comics are sprinkled with speech and thought bubbles, they actually produce no sound. Moreover, all these speech bubbles are visible at the same time on the panel, but readers understand that this text follows an order, just like the images. Each panel is a snapshot of a moment that the mind connects with the one before and the one after, under the established convention of the medium that these images represent a chronological sequence. So how does this all play out, and what effect does it have on the story? In short, it plays with the metatextual expectations of speech in comics.

Credit: Kaiju

A two-panel page.

First panel: Sulvain and Viverette are looking at each other as they hold a conversation in signs.

Second panel: Viverette are facing Éve, who is off panel. Sulvain is holding up his closed hands together, index fingers pointing up as Viverette speaks.

Viverette: If they have need for my services, I will meet them here.

Credit: Kaiju

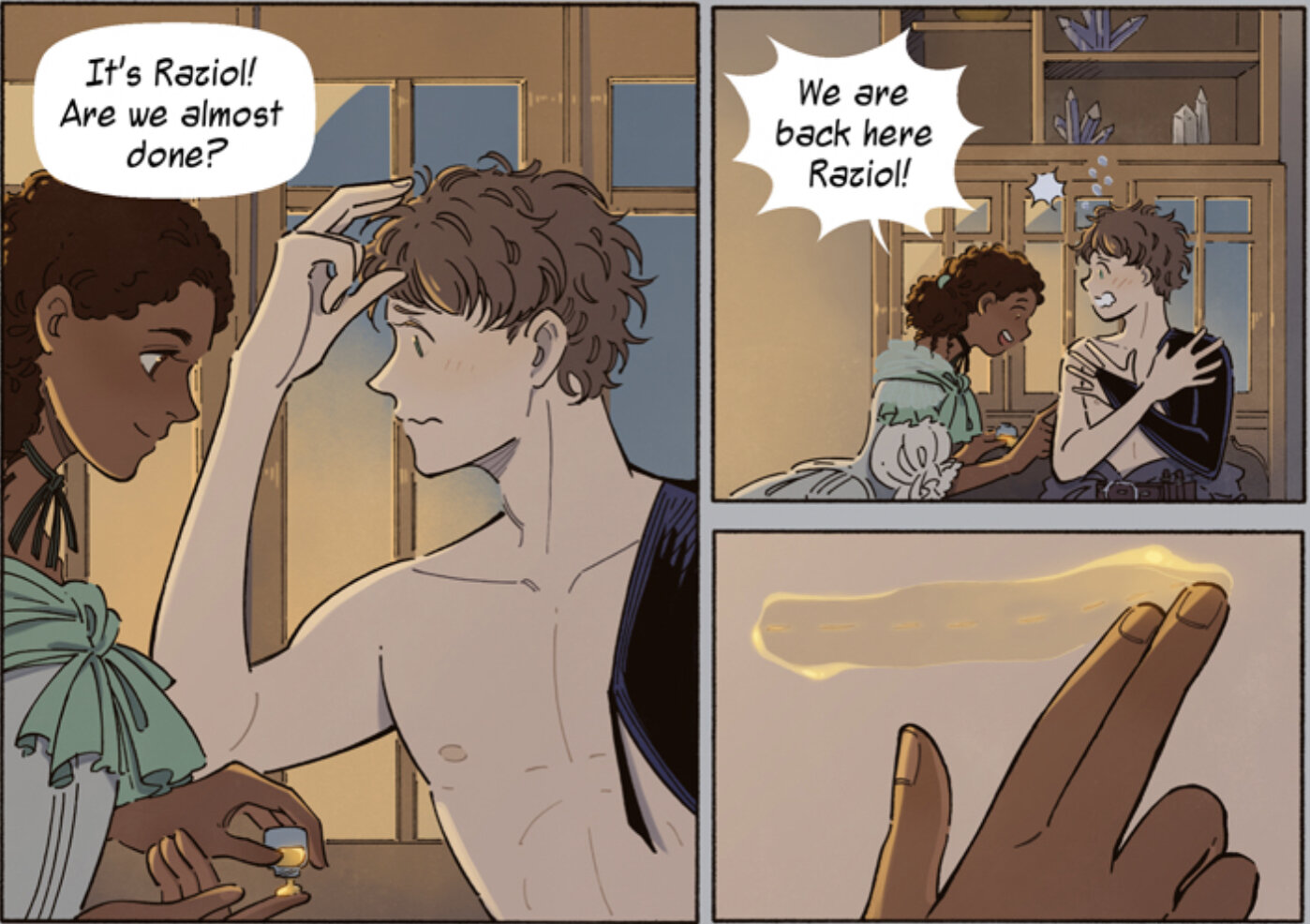

A three-panel page.

First panel: Viverette is pouring a small amount of a golden substance on her finger as she looks at Sulvain endearingly. Sulvain is shirtless and holding his right hand over his head to sign. He is both nervous and eager.

Sulvain: It’s Raziol.

Second panel: Vivertte is rubbing the golden substance on Raziol as she gleefully calls out to Raziol. Sulvain is surprised and covers up his naked torso with his hands.

Viverette: We are back here Raziol!

Third panel: A close-up of Viverrete’s finger as she rubs the golden substance over Sulvain’s stitched wound.

In comics, the text displayed in speech bubbles and thought bubbles are accepted as an absolute truth: these are the words coming out of this character’s mouth in this moment. With Sulvain’s speech bubbles, there is a degree of interpretability in between. Are the words a one-for-one translation of his signs? Are they the creator’s interpretation of the signs? Or are they Viverette’s personal interpretation of them? These are all plausible; however, this last possibility seems to add the most to the dynamic between both characters. In the first panels, Viverette would be complimenting herself through Sulvain’s comments, but brushing the compliments off at the same time. In the second group of panels, Viverette is stressing the firm and determined tone of Sulvain’s curt signs to Ève. In the last panels, Viverette knows exactly what Sulvain means even when he just signs Raziol’s name. This kind of dynamic this interpretation presents does nothing but strengthen the bond that these two have for each other. The reader in turn is able to experience a deep friendship where thoughts can be shared by a simple glance.