Cosmoknights by Hannah Templer is the story of run-away mechanic Pan and her journey to find her friend Tara, the missing princess of their homeworld, who Pan helped escape years before. Pan teams up with Cosmoknights Cass and Bee, warriors for hire that compete in battle royals to win a princess’s hand in marriage. Instead of delivering the princess to their client though, Cass and Bee let the princess go to live her own life. Soon after teaming up with Pan, their group gains a fourth member in Kate, who proposes that simply spiriting the princesses away is not enough, and that the entire tradition of jousting must be eradicated for princesses to truly be free.

How does the use of reflections develop Cass’s backstory?

The use of reflections to symbolize the search of identity is a tale as old as time — wait, wrong movie. It is a timeless device for those struggling to show who they are inside — there we go. Reflections prove to be effective narrative tools because, on the one hand, the character experiences the uncanniness of confronting their subjectivity with an outward self they may not identify with. On the other hand, the reader is able to observe the process of negotiation between the subject and the reflection. This is specifically true in visual media such as comics as the way a panel is composed to feature both elements, the subject and the reflection, adds an additional insightful frame to the character’s story. As such, panels depicting moments of literal and symbolic self-reflection can be incredibly layered with significance.

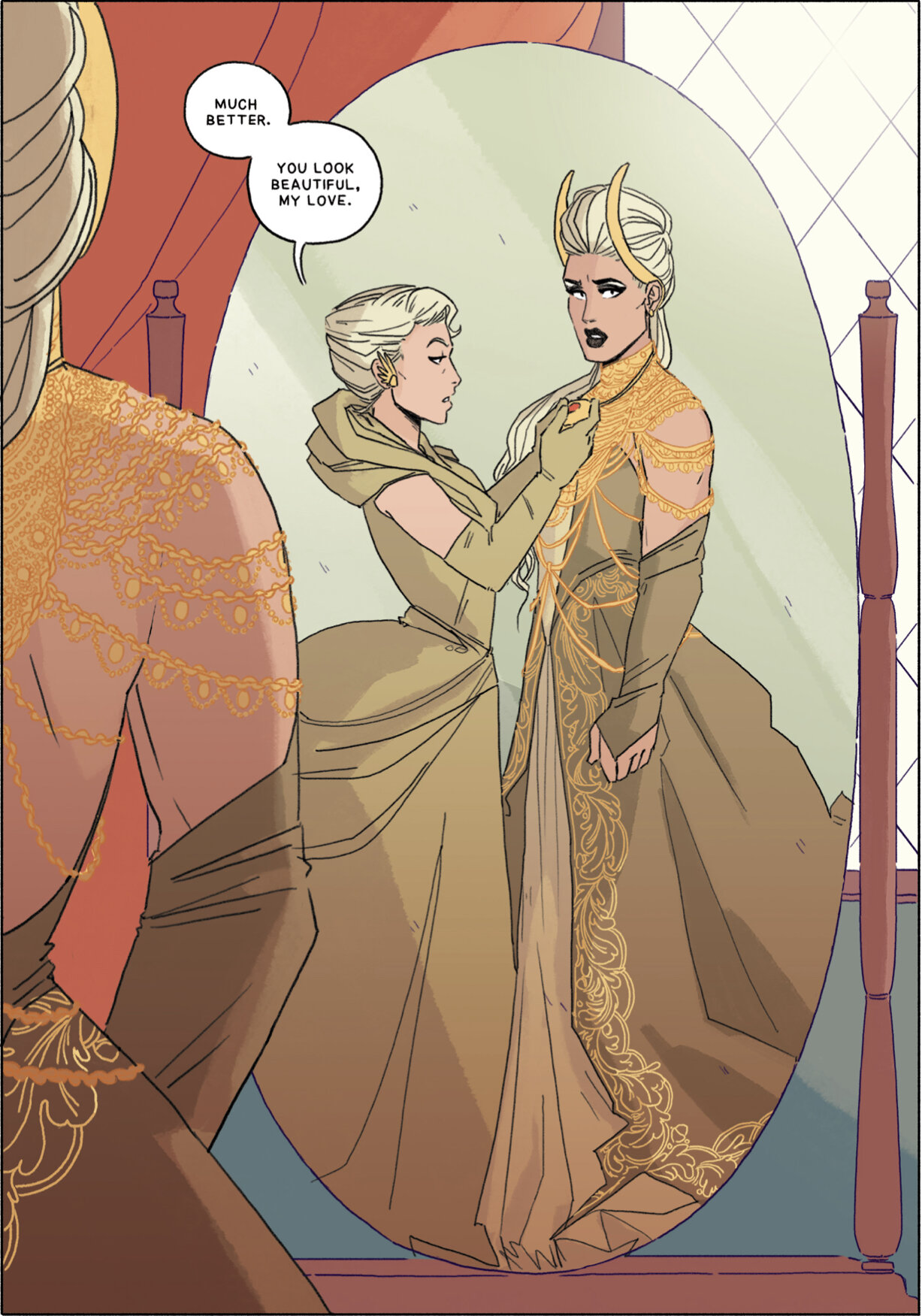

Credit: Hannah Templer

A full-page panel.

In the foreground, on the left edge of the panel, Cass’s right side of her back is seen. Her strong, defined shoulders and arms are draped with fine gold chains. In the background, Cass is looking at herself in a full-body mirror as her mother places her favor around her neck. Cass is looking as if she doesn’t recognize her reflection, dressed in a long olive green gown, trimmed with ornate gold stitching. Her bodice is laced with a series of fine gold necklaces that web around her.

Queen: Much better. You look beautiful, my love.

The panel above is the product of Cass’s grooming and polishing after a fierce and energetic training session with her father. It is a full-page panel that not only fully depicts Cass’s transformation, but it also allows the depiction to be presented upon a full-bodied mirror. This panel could have been composed differently, for instance, as a break-out illustration or simply as is with the dressing room as a background. Why use a full-body mirror? Because it succinctly frames Cass’s dilemma both literally and figuratively. With the addition of her mother, the mirror becomes a symbol of familial expectations. The real Cass is only featured partially from behind, obscured from the viewer. The reflection, which Cass is apprehensive about, is the way her family sees her — or rather wants to see her. Her mother also functions as an additional reflection as she represents Cass’s future and duty, which she also doesn’t identify with. She is her mother’s daughter, dressed in the same colors, draped in golden chains that, at the end of the day, are chains nonetheless.

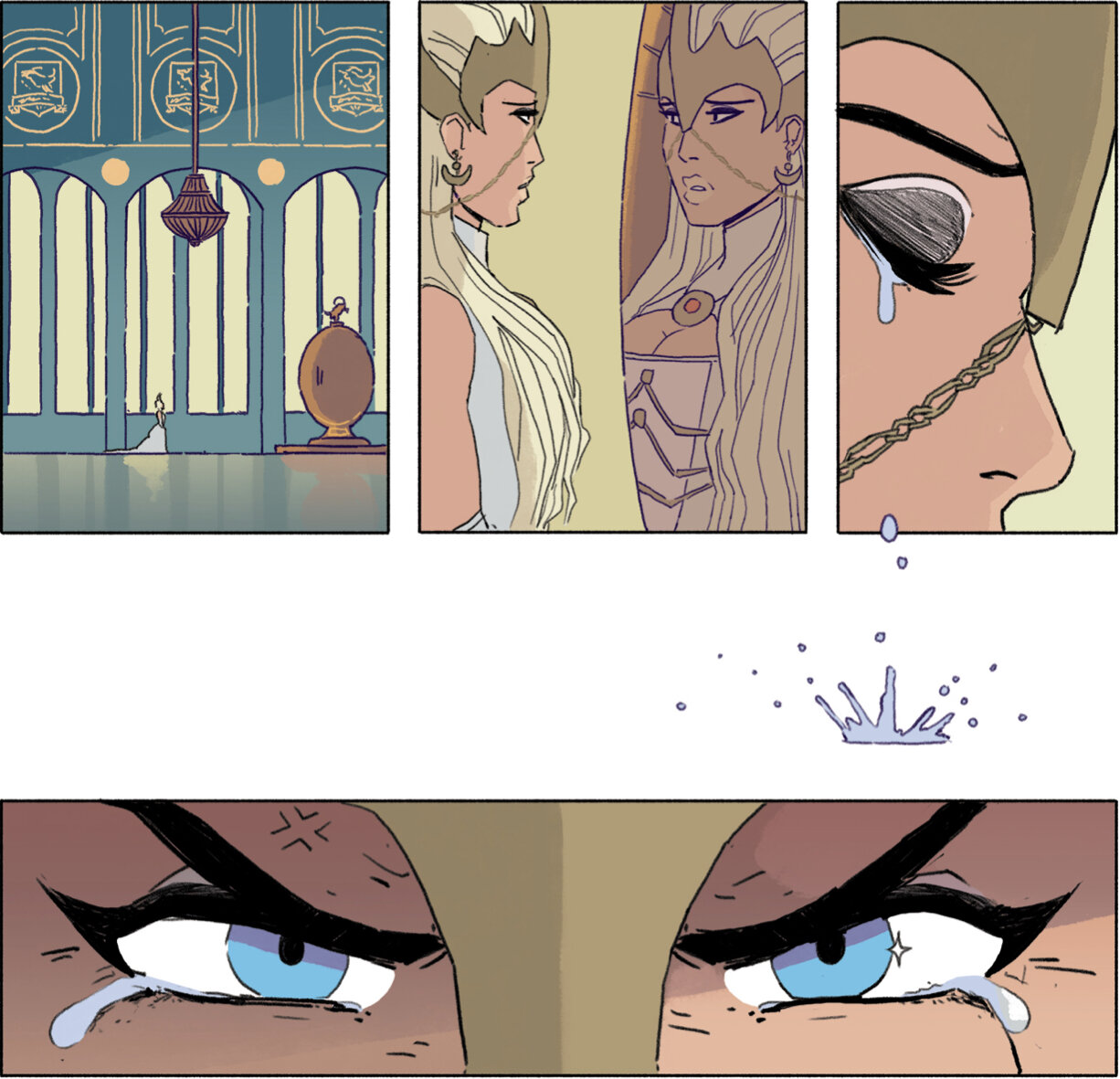

Credit: Hannah Templer

A five-panel page.

First panel: A far shot of a hallway as Cass faces the throne encased in its egg-shaped gold capsule.

Second panel: Cass gazes sadly at her reflection upon the gold surface of the capsule.

Third panel: A profiled close-up of Cass’ closed right eye shedding a tear.

Fourth panel: A breakout illustration of a tear falling on a surface. The tear is an extension from the previous panel.

Fifth panel: An extreme close-up of Cass’s eyes. The are tear-filled, with sharp make-up, and full of righteous determination.

Credit: Hannah Templer

A two-panel page.

First panel: Cass picks up the helmet. Her determined face reflecting off the visor.

Second panel: A close-up of the helmet as Cass’s reflected face is perfectly framed by the visor and lower frame.

The next instance of Cass’s reflection carries similar symbolism. She looks at herself reflected off the golden surface of the capsuled throne. She is already in a massive and ostentatious hall, proof of her family’s power and position, and the egg-like capsule is nothing but a gilded cage she is expected to climb into merrily. Cass’s reflection on this shiny object represents the literal objectification she is undergoing. Her subjectivity is stripped away to become nothing but an object to be boxed up and won. It is no surprise when this is the moment when Cass decides to finally claim her own subjectivity through her own agency. After rushing to her family’s armory, she sees herself on the helmet’s visor. In contrast to the other surfaces, this one fits her perfectly. It doesn’t feature her body or any sign of acquiescence. It is nothing but her passionate and determined gaze upon an object that reflects her true self back.