Heartstopper is a coming-of-age love story by Alice Oseman. After a year of bullying after being outed, Charlie Spring starts a new year at Truman Grammar School for Boys. Here he meets and befriends Nick Nelson, an upperclassman who — much to Charlie’s bewilderment — is nothing but absolutely friendly and kind to him. As they become closer friends each passing day — as well as teammates on the rugby team at Nick’s insistence — Charlie can’t help but fall for the ever-growingly affectionate yet presumably straight Nick. As Charlie tries to keep his feelings in check, Nick finds himself unable to keep away from Charlie and starts on his own journey of self-discovery and acceptance.

How does Charlie’s relationship with Ben create a strong, relatable character?

As media with queer characters becomes increasingly (and thankfully) common, one trope that continues to stand true is that of the outcast. In fact, this works for stories of all shapes and forms regardless of their characters’ sexuality as most people, at one point in their lives, have felt like they don’t belong or were rejected from a space thought to be their own. Now, an important distinction needs to be made: experiencing rejection due to actions or behaviors that purposefully hurt someone else emotionally or physically does not an outcast make. A clear and spoiler-y example of this is how Harry Greene is unwelcome at the Paris sleepover after always being horrible to Charlie, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. An outcast is a person who suffers rejection due to factors outside of their control such as cultural background, race, skin color, and sexuality. Because of the way sexual minorities have been treated historically, the outcast character trope is almost eponymous with queer media.

Credit: Alice Oseman

A three-panel page with two individual speech bubbles.

First panel: Charlie is with two nondescript students, who appear to be laughing or jeering at him.

First bubble: “He’s been getting a lot of shit for it, I think.”

Second panel: Nick looking anguished, watching the previous scene from afar.

Third panel: A profiled shot of Charlie being confronted by bunched-up speech bubbles with slurs and insults towards him.

Second panel: “I mean, this is an all-boys school! What did he expect?”

Heartstopper brings an interesting perspective to the trope. Different characters point out that Charlie is popular and generally well-liked, but this is after a grueling year of bullying after being outed. As discussed previously in this blog, being outed is a traumatic experience as it deprives the person the agency of coming out when they’re most comfortable and under their own terms. This agency is crucial as it counters the social pressure that keeps the person in the closet. Being outed leaves the person exposed and vulnerable without the right support, which is what happened to Charlie. An all-boy’s school is a traditional space for hegemonic masculinity to be learned and maintained, and one of the tenants of it is compulsory heterosexuality and homophobia. As such, Charlie became a scapegoat, a figure to be cast out and be made an example of so the group at large could strengthen its bonds and reaffirm its values. While the harrowing seems to be mostly over when the story begins, he still deals with the aftermath of it as seen with his relationship with Ben.

Credit: Alice Oseman

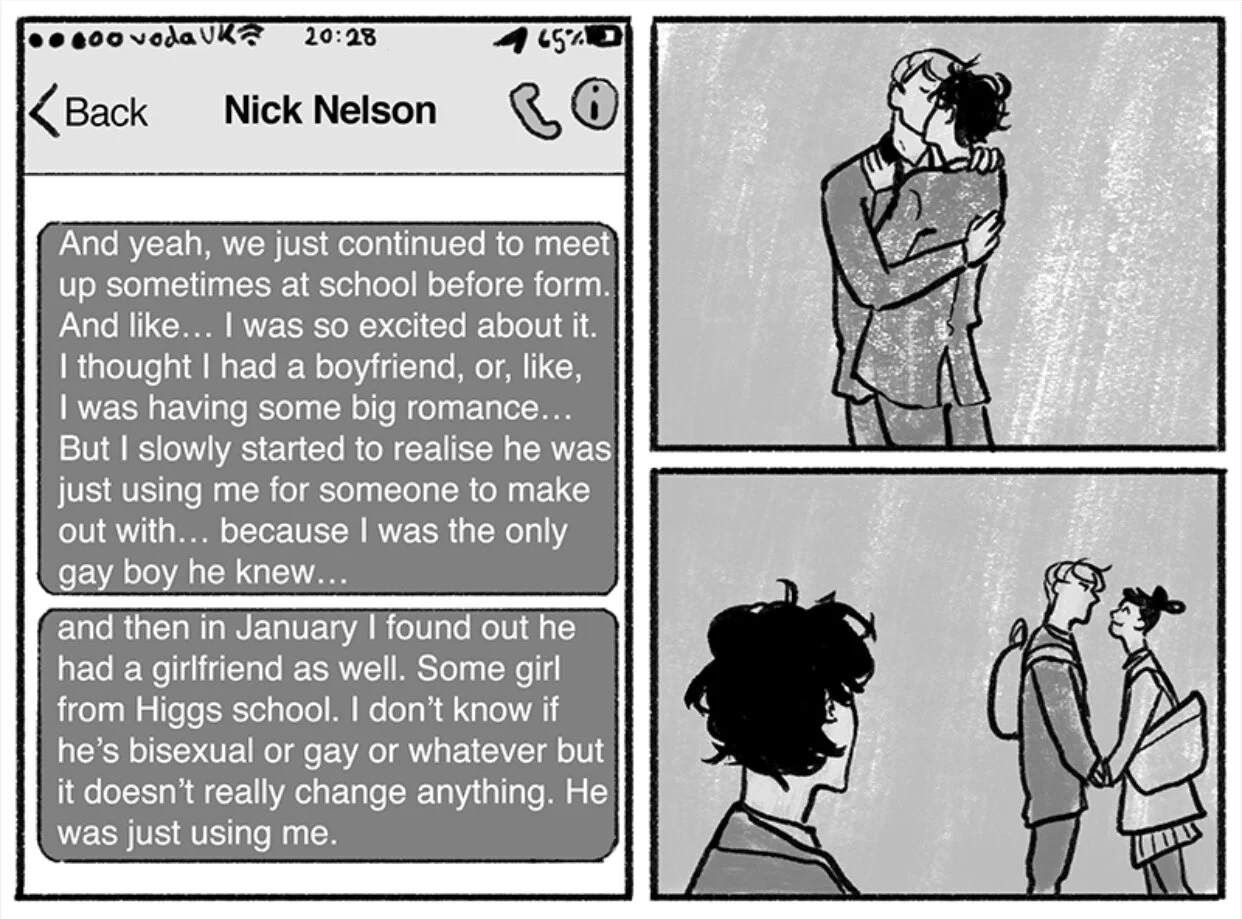

A three-panel page.

First panel: And text screen on a phone, under the name of “Nick Nelson”

Charlie:

A yeah, we just continued to meet up sometimes at school before form. And like… I was so excited about it. I thought I had a boyfriend, or, like, I was having some big romance… But I slowly started to realise he was just using me for someone to make out with… because I was the only gay boy he knew…

and then in January I found out he had a girlfriend as well. Some girl from Higgs school. I don’t know if he’s bisexual or gay or whatever but it doesn’t really change anything. He was just using me.

Second panel: Charlie and Ben locked in a hug and kiss.

Third panel: Ben is holding hands with a girl, staring into each other’s eyes, as Charlie watches from afar.

Credit: Alice Oseman

A seven-panel page.

First panel: Ben is coming up to Charlie, who seems surprised and distances himself.

Ben: Look, I’m sorry, okay? Have you finished sulking about it?

Second panel: Charlie determinedly passes Ben, who is grinning.

Charlie: Leave me alone.

Third panel: A close-up of Ben’s hand as he grabs Charlie’s arm.

Ben (off-panel): Oh come on, Charlie!

Fourth panel: A close-up of Charlie’s face as he looks over his shoulder.

Fifth panel: A close-up of Charlie grabbing Ben by the front of his shirt, slamming him against the wall.

Sixth panel: A shot of Charlie looking furious with wide eyes, and narrowed eyebrows. The backdrop around him is pitch black.

Charlie: Do not fucking touch me.

Seventh panel: A shot of Ben dumbstruck, still holding up his left hand, frozen against the wall Charlie slammed him against.

The kind of relationship Charlie has with Ben can be too close for comfort for many people. It is completely one-sided, with Ben taking complete advantage of Charlie’s loneliness and vulnerability while he remains in the closet, and with Charlie mistaking Ben as a fellow outcast, and a legitimate source of care and comfort that validated and appreciated him. The trips and stumbles Charlie experiences are all too relatable for many; they are all too common consequences of being subjected to an environment that is unwelcoming to difference. Charlie soon sees Ben for what he is, and he makes a critical shift between objectivity to subjectivity. In other words, he stops being and seeing himself as an object to be ridiculed and taken advantage of to being his own person with needs and wants. This is ultimately what the coming out process is: the act of self-determining regardless of societal expectations. In this first phase of his journey, Charlie has started to confront his past which all readers can familiarize themselves with.