Tiger, Tiger, created by Petra Erika Nordlund, tells the story of Ludovica Bonaire who steals her family ship to fulfill her wish of studying sea sponges. Ludovica is the scientifically-curious and adventure-starved heiress to a noble merchant family, and as such she is unable to travel the world to see her beloved sea sponges in the wild. With the very reclunctant aid of her arranged fiancé Jamis Arlesi, Ludovica steals her family’s ship disguised as her own brother Captain Remy Bonaire, who Jamis serves as first mate. During the journey, Ludovica discovers Remy’s diary and whole new side to Remy he has kept to himself.

Why introduce the concept of queerphobia to a queer story?

In earlier entries, this blog has discussed the power a creator has to eradicate queerphobia from their texts. The decision to eliminate any negative notion surrounding non-heterosexual people can mostly stem from two factors. One, the story simply does not require any notion of negativity towards queerness; or two, the decision is a direct response to the assumption that a queer text must always tackle the issue of oppression from heteronormativity. The two are not mutually exclusive, of course. Whatever the reasoning may be, many queer and ally creators wish to explore stories set in worlds and societies where queerness is a non-issue, even in those texts that fall within more realistic settings. For many readers, it is often disappointing that stories set in more fantastic worlds, where the creator can let their imagination go wild, queerphobia exists. It often feels like a direct message: queer people will always be rejected. So, if a creator has the power to create the world of their dreams, where queer characters are the protagonists, why introduce notions like queerphobia into the world?

Credit: Petra Erika Nordlund

A two-panel page.

First panel: A shot of baby Remy in a large, plush bed. His father is seen from behind as he sits on the bed, facing Remy.

Remy’s father: You shouldn’t say… People might take such things the wrong way, you know? How do I explain this…

Second panel: A shot of Remy’s father, as seen from Remy’s perspective. He has a soft and understanding look of his face.

Remy’s father: Remember, Papa will always love you, no matter what. But… other people… It might look like all those men are papa’s friends, but it isn’t always so.

Briefly put, because adding negativity serves as an outlet for the creator, which in turn serves as an opportunity for identification and catharsis for the readers. In the same way that creating a world completely devoid of queerphobia acts as a response to its real world prevalence, engaging it in a fictional environment is also a direct response in a safe space. A creator can make use of their own lived experiences or those around them regarding queerphobia to create similar fictional situations, allowing the exploration of different characters’ reasonings and behaviors. In turn, readers can identify with characters who experience similar hardships than they have. In the panels above, a young Remy is cautioned by his father that his vocal interest in men can be misconstrued by some and cause him problems. This serves as a formative moment for Remy since, before that conversation, he had been completely innocent. From that point on, he gained a notion that there might be something wrong with him. This is a moment that all queer people experience in some shape or another.

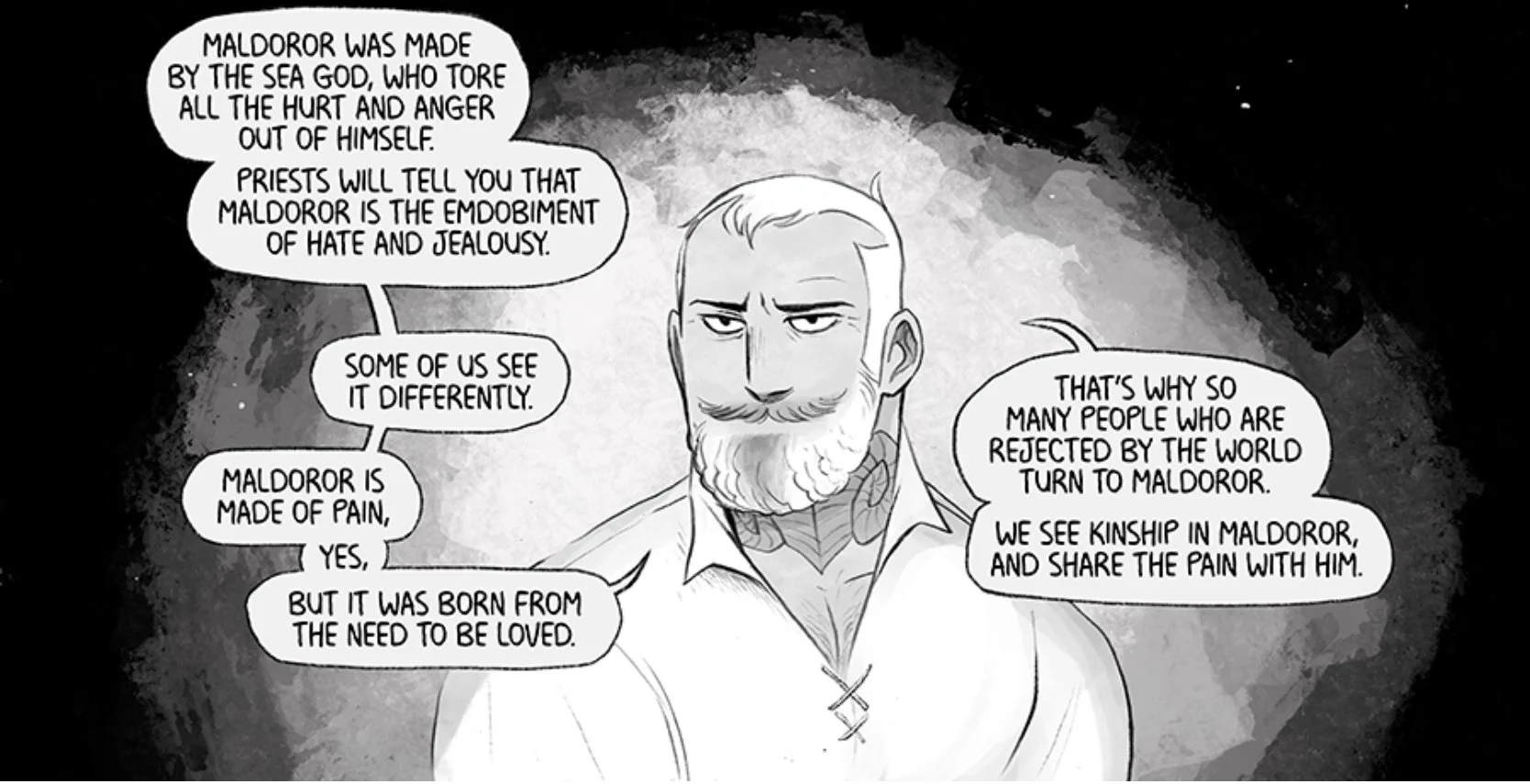

Credit: Petra Erika Nordlund

A single panel.

A shot of Arno as he faces and talks to Remy. In the backdrop, Arno is surrounded by a blurry halo of light against pitch-black darkness.

Arno: Malodoror was made by the sea god, who tore all the hurt and anger out of himself. Priests will tell you that Malodor is the embodiment of hate and jealousy. Some of us see it differently. Malodoror is made of pain, yes, but it was born from the need to be loved. That’s why so many people who are rejected by the world turn to Maldoror. We see kinship in Malodoror, and share the pain with him.

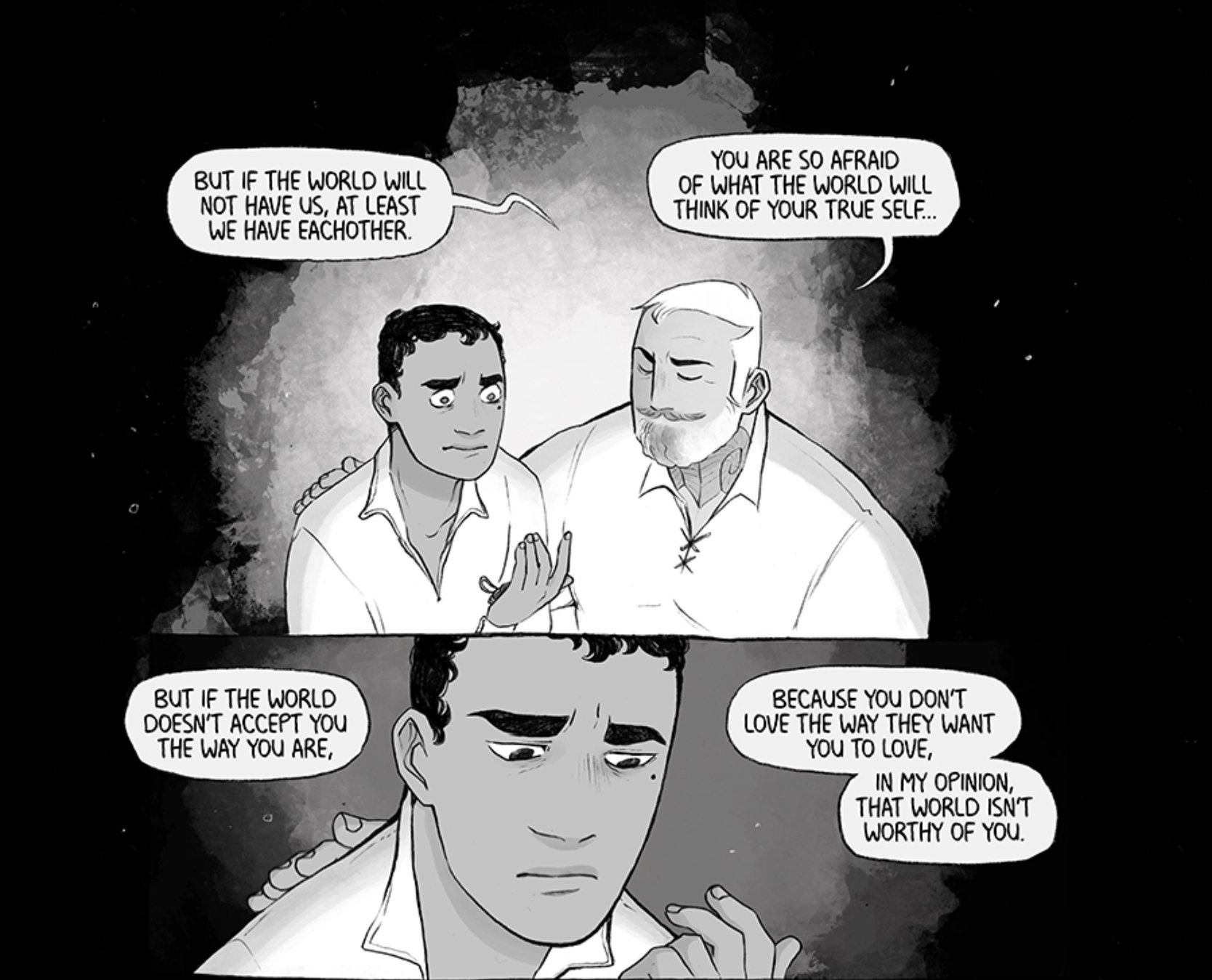

Credit: Petra Erika Nordlund

A two-panel page.

First panel: Arno has his hand on Remy’s shoulder. Remy’s face is quivering with emotion as he looks at the knot charm in his palm Arno has just given him.

Arno: But if the world will not have us, at least we have each other. You are so afraid of what the world will think of your true self…

Second panel: A close-up of Remy’s sullen face, still looking at the charm in his palm.

Arno: But if the world doesn’t accept you the way you are, because you don’t love the way they want you to love, in my opinion that world isn’t worthy of you.

Now, from a narrative and storytelling point of view, creating a world with negative notions that influence characters’ beliefs and actions are necessary for effective world building. A cornerstone of the mythos of Tiger, Tiger is the threat of Maldoror, a creature created from the negative emotions of the God of the Sea. Maldoror has been a threat to humanity as it lashes out in envy and hurt, as such having a world completely devoid of these emotions in the characters would be disingenuous to the story’s own mythos. Despite Maldoror being an embodiment of the emotions that lie at the heart of queerphobia, as explained by Arno, many social outcasts actually pay tribute to Maldoror instead of the Gods of the Land and of the Sea. People like Arno don’t focus on what Maldoror embodies, but rather on what brought it to the world: the need to be loved. The deep sense of identification that Arno and other believers have with Maldoror mirrors the level of identification that readers’ can have with the characters and story themselves. In the end, in the same way the queer community stands for diversity, the same holds true for the variety of stories we can tell and enjoy. We need the bitter as much as we do the sweet.